Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

GLOBAL BANKING CONTAGION:

WERE SA BANKS AT RISK?

The global banking turmoil triggered by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and two other US banks, followed by the failure of Credit Suisse across the pond, saw banking shares sell off across financial markets in a matter of days. South African banks were not spared the tumult. Contagion fears grew, and memories of the 2008/09 global financial crisis (GFC) came flooding back. Should investors be concerned about a spillover effect on the local banking sector, or did our banks largely escape the fallout?

In our view, the stresses currently being experienced within the US banking system are idiosyncratic – they’re the result of, first, rising interest rates, and second, regulatory failure. Let’s take a closer look at events as they unfolded.

A bank’s business model entails borrowing over the short term (deposits) to lend for the long term (loans) – this makes a bank susceptible to a range of risks, which exposes its solvency. The stress experienced by the US banking system can be ascribed to both market risk (unrealised losses on the investment portfolio, exacerbated by rising interest rates) and liquidity risk (when the bank can’t meet the liquidity requirements for customer withdrawals due to the illiquidity of its assets). Credit Suisse’s difficulties stemmed from the mismanagement of all four major risks faced by banks: market, credit, liquidity and operational risks.

The first bank to topple in the US was SVB, a niche player uniquely dependent on the growth of technology companies and the financial health of the tech industry. Its customer base was therefore not well diversified like that of many mainstream banks, and the bank ultimately ran into trouble due to losses on its investment portfolio.

SVB had invested customer deposits in longer-dated US government bonds to earn higher yields and had attracted significant customer deposits when interest rates were low, creating a liquidity mismatch. Given the rapid rise in US interest rates over the past 12 months, bonds held by SVB decreased in value (rising interest rates cause bond prices to decline), leaving a gaping hole on its balance sheet as it was forced to sell some of its bonds and realise a significant loss.

The news sparked fear and loss of confidence by the bank’s customers – largely tech companies and wealthy individuals – around the bank’s liquidity, which ignited a run on the bank and ultimately forced it to close. The US Federal Reserve intervened swiftly and guaranteed all SVB depositors in order to stabilise the banking sector.

SVB was the first domino to fall, followed by Signature Bank, while Silvergate Bank announced voluntary liquidation (it’s important to note that the latter two banks were large lenders in the crypto sector, and therefore not players in the tech space like SVB was – but after the collapse of the exchanges, they succumbed to a similar fate). Banks can, and have, survived scandals, financial losses and economic downturns, but a bank run is more or less guaranteed to end the party.

In Europe, losses from Credit Suisse’s shares added to the instability of markets as investors worried about the bank’s liquidity. The second largest Swiss bank had been plagued by several scandals over the years, including significant losses during the Covid-19 pandemic, resulting in a dip in confidence by customers who started to withdraw deposits towards the end of 2022.

The fall of Credit Suisse had been in the making for several years, but the straw that broke the camel’s back was the decision by the bank’s partner, Saudi National Bank, that it would not be providing more money to shore up liquidity. The regulator stepped in and ultimately forced the takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS to bring stability to the Swiss banking sector.

While these events have certainly highlighted financial stability risks within the banking system, the situation is fundamentally different to the GFC. Before 2008, banks in general were inadequately capitalised and had far more exposure to credit risk due to poor lending practices. Today, banks hold much more capital to weather adverse shocks and credit risk has been reduced by more stringent post-crisis regulation.

A major factor in the current crisis has turned out to be regulatory oversight. However, it should be pointed out that this oversight occurred only within a specific region, and it applied to a particular category of bank.

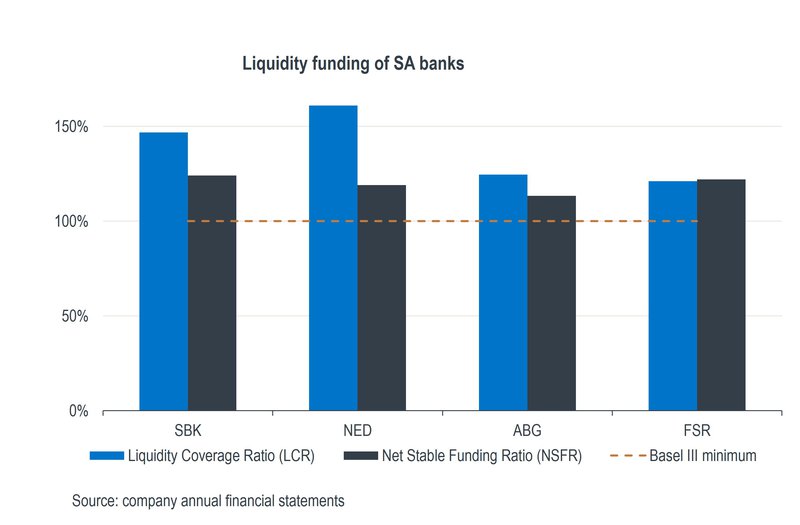

In the US, regional banks were allowed to circumvent certain requirements stipulated by the Basel III global regulatory framework for banks, in particular two important liquidity ratios: the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), which ensures that banks have enough liquid assets for a 30-day stress scenario, and the net stable funding ratio (NSFR), which ensures that banks have reliable funding sources in stressed environments.

As of January 2019, in terms of Basel III, the LCR and the NSFR are both required to be equal to at least 100%. These ratios address both the asset and liability side of a bank’s balance sheet. In the case of the US regional banks, they were allowed to fall below 100% on an ongoing basis. When the environment became stressed, the banks suffered a liquidity issue, which led to insolvency.

It’s too early to say for certain whether further cracks will appear in the global banking sector. Fortunately, regulators have acted with haste by providing financial support and guaranteeing deposits to restore confidence in the system and prevent contagion.

What we do know is that the need for financial regulation and governance is rarely more evident than during a crisis. This was certainly true after the GFC, when Basel III was implemented to tighten capital requirements for banks.

We would now expect more stringent lending practices by all banks (including smaller, regional banks) as they begin to rebuild trust and confidence among their customers. In addition, given that banks are part of the fabric of society and help drive economic growth, regulators will be studying the recent turmoil to fully understand what occurred. We anticipate increased regulation surrounding capital and liquidity requirements, especially for US regional banks, as well as a focus on deposit insurance across jurisdictions.

Lastly, we think there will be a greater focus on the speed at which depositors are able to access their deposits, which has increased significantly over the past 10 years with the rise of digital banking.

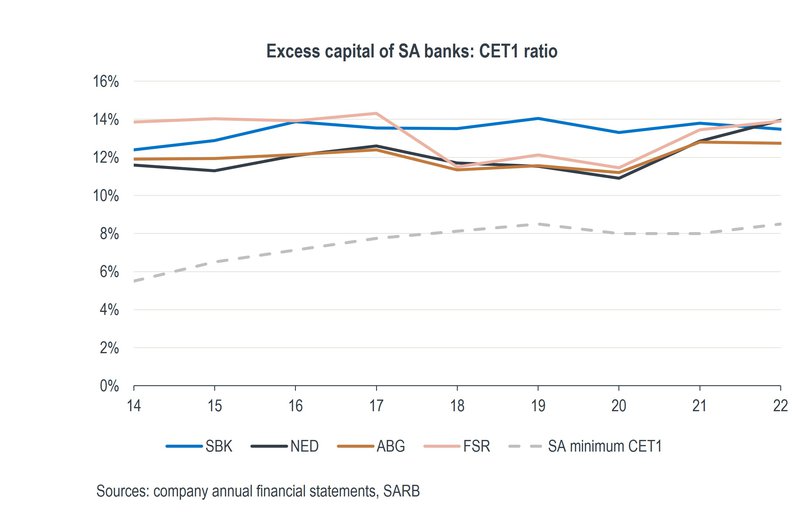

The crucial question for South African investors is how the recent global banking drama has impacted our own banking sector. One way of assessing a bank’s ability to endure financial distress is by looking at what’s known as the common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio, and as can be seen on the chart below, the four big players in the South African banking sector (Standard Bank, Nedbank, Absa and FirstRand) remain well capitalised.

Our banks are well above the South African Reserve Bank minimum (excluding idiosyncratic requirements), which exceeds the Basel III minimum CET1 of 4.5%. Local bank board targets range from 11% to 12%, which speaks to the conservative nature of our banks’ management teams and their ability to navigate a challenging economic environment.

Furthermore, South African banks are subject to stringent regulation, and they’re accustomed to operating in an environment of higher interest rates and elevated inflation. While our banks face their own unique challenges within South Africa, poor regulatory oversight and solvency issues are not among them. Our large banks have proven to be resilient, forward-looking with regard to bad debts and well managed over time.

We mentioned earlier that US regional banks did not have to comply with Basel III regulations regarding liquidity ratios, which are required to be above 100%. As can be seen on the chart below, the four major South African banks remain well above the Basel III minimums in terms of liquidity funding.

From an investment point of view, at Sanlam Private Wealth we remain constructive on the South African banking sector, which is currently trading at low valuations. We believe that in times of turmoil and market panic, opportunities tend to present themselves – we will make use of these and add to our clients’ portfolios in the sector where appropriate, enhancing returns over the long run.

Your wealth plan is designed with you in mind. Your financial reality, aspirations and risk profile.

Carl Schoeman has spent 22 years in Investment Management.

Looking for a customised wealth plan? Leave your details and we’ll be in touch.

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.