Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

INVESTMENT RETURNS:

HAVE THE DRIVERS CHANGED?

Long-term investment returns are driven by a host of factors – from macroeconomic considerations to various company-level variables. In our view, many of these are directed by the actions of three main players – central banks, company management, and market participants – which have evolved significantly over the past 50 years. How have these changes impacted returns, and have they influenced the way we think about investments?

The macroeconomic elements that impact long-term investment returns include economic growth, inflation, interest rate changes and exchange-rate fluctuations, while at company level, factors such as business growth, return on capital, valuation change and dividend yield play an important role. Many of these variables are shaped primarily by three crucial ‘drivers’:

How have these drivers evolved over the years, and what are investors to make of these changes?

For more than a century, the international monetary system was based on what was known as the ‘gold standard’ – the value of individual currencies was linked directly to a physical commodity: gold. From 1931, however, the gold standard was abandoned by one country after another, with the US dropping the system in the early 1970s.

For the past 50 years, central bankers have been working with a currency system known as ‘fiat money’, where currencies are issued by governments as legal means of payment. The argument is that a national currency backed by the government rather than a commodity gives central banks greater control over both the money supply and the economy.

What has been the effect of the abolition of the gold standard and its replacement globally by national fiat currencies? For one thing, it has reduced the number of economic recessions, especially in the US – since 1972, that country has experienced only seven recessions compared to 11 over the preceding 50 years.

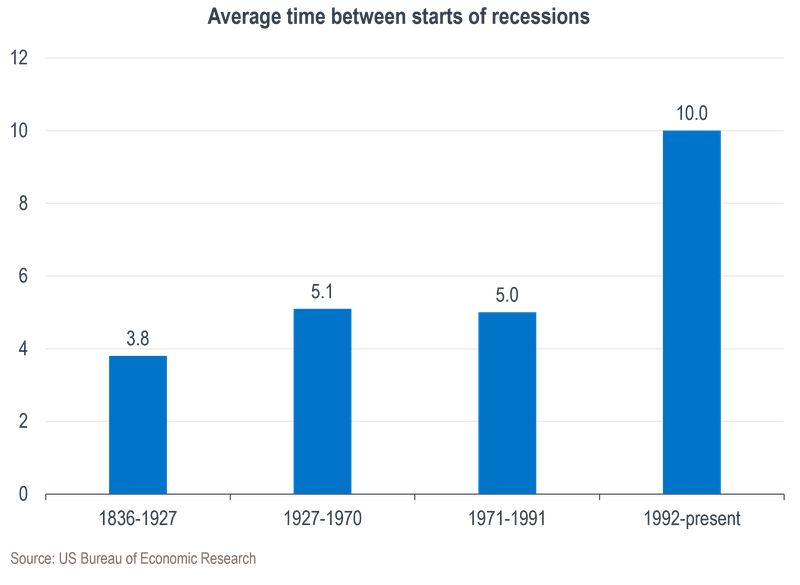

Furthermore, the time periods between recessions in the US have been increasing. For the first 20 years after the arrival of fiat money, the average time from the start of one recession to the next was five years, but since 1992, this gap has widened to 10 years, as can be seen on the chart below:

While economic cycles will always be with us, if the trend indicated in the chart continues, these cycles are likely to be longer over the next 50 years than they were over the previous 100.

Of course, having fewer recessions means a reduction in the number of data points on which central banks can base their decision-making. However, central banks nowadays have far superior information to work with when deciding on monetary policy than in earlier years. As central bankers have gained more experience of managing fiat money systems, they’ve learnt what (mostly) works and what doesn’t.

What does this mean for investments? Essentially, investors will need to think in terms of longer economic cycles – but it also means that investment cycles are likely to have greater amplitudes on both the up- and the downside. This will probably result in fewer but more dramatic buying and selling opportunities in the coming decades.

There are few jobs more Darwinian – where the survival of the fittest is paramount – than that of CEO of a major listed company. Our capitalist system means that top managers who don’t perform will ultimately be shown the door. In a competitive, dog-eat-dog world, businesses must relentlessly and consistently improve – just to stand still in relative terms.

The roles and functions of company leaders have evolved significantly over the past half a century. Today’s managers are generally more educated and understand money far better than their counterparts in earlier years. Managers in the 1970s were typically engineers, while the modern CEO’s job is mainly about capital allocation. As an example, there are now more than 250 000 MBA graduates each year globally, around five times as many as 40 years ago.

It’s only in this century that the most common method for company managers to decide whether to invest in a project has shifted to internal rate of return (IRR) from traditional considerations of payback period. The switch enables managers to make more effective decisions about capital allocation, especially for projects with longer lead times and deeper J-curves.

This change can be seen most clearly in the behaviour of mining companies. These management teams certainly learnt their lessons after the commodity price lows around 2016. The industry invested heavily in expanding production during and after the 2000-2011 commodity supercycle, and then suffered the unsurprising pain of low prices in an oversupplied market for years thereafter. As usual, once prices crashed, investment dried up. The key change, however, is that as prices rose again between 2017 and 2022, high investment in new mines didn’t follow – the ‘usual’ cyclical factors around expanding supply are therefore less at play than the historical norm.

While the environment in which today’s companies have to do business will of course remain highly competitive in the years to come, capital allocation should continue to improve incrementally over time, particularly in more cyclical industries – positively impacting long-term investment returns. Companies in cyclical industries are likely to make better long-term decisions than they did in decades gone by, thereby both extending the length of such cycles and potentially delivering better through-the-cycle returns to shareholders.

Finance is a relatively new discipline. Although investment markets have been around for hundreds of years, the mutual fund industry in the US only really took off in the 1970s, and two decades later in South Africa. Before this, many people managed their own investments with limited professional advice, or entrusted their money to a few large insurance companies.

The study of investment management got going around the time that Benjamin Graham’s seminal work The Intelligent Investor was published in 1949. Graham’s teachings around finding anomalies, like companies trading for less than the net cash on the balance sheet, were the foundation of Warren Buffett’s investment philosophy. As Graham’s original ideas entered the mainstream, their usefulness as a source of ‘edge’ in the industry dried up. Buffett has accordingly evolved Berkshire Hathaway’s process and philosophy to find new ways to beat the market.

Peter L Bernstein’s book Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (which I recommend only for the deeply curious and mathematically minded) highlights that modern probability theory was developed only in 1933 by Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov and translated into English in 1950.

The point here is that much of the academic foundation for the fields of finance and asset management is relatively new. At the same time, many data series go back fewer than 30 years – forward price-earnings multiples being an obvious example.

The Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) qualification, which is now considered the standard in investment management, has been around only since the 1960s. As recently as 1983, fewer than 400 people were awarded the qualification globally. By 1997, around 2 000 people per year were qualifying as CFAs, and this number has since expanded to about 20 000 per year. For some context, India and China currently produce a combined ~2.1 million engineers each year.

Not only have we become ‘smarter’ in a relatively short space of time, but the rise of real-time information and the increasing ability to process huge amounts of data rapidly mean that historical sources of outperformance have been competed away.

The impact of this can be seen in the growing number of very sharp moves in stock prices (for example, Meta shares dropped by more than 20% in both February and October last year). Where previously it might take the market days or weeks to fully incorporate new information, it now takes place in a matter of minutes or hours. We expect this trend to persist. With no advantage to be gained from reacting quickly, this ironically means that more ‘edge’ should be available to investors who think long-term.

Markets are likely to continue to evolve. It’s important to remember, however, that while history often ‘rhymes’, as Mark Twain said, the future will have its own idiosyncrasies.

In our view, there are two things that will not change in the investment world:

These two factors form a major part of where we at Sanlam Private Wealth see our source of edge. Our process and philosophy are focused on investing for the long term, with the aim of finding businesses that will consistently deliver returns above their cost of capital. Paying the right price for such businesses is crucial, and the increasing potential for extremes created by more volatile markets helps us in this regard. There is always opportunity amid turmoil – if one has the fortitude to look through the short-term noise, both positive and negative.

We provide daily reporting of trades, monthly portfolio evaluations and annual tax reports to clients.

Riaan Gerber has spent 16 years in Investment Management.

Looking for a customised wealth plan? Leave your details and we’ll be in touch.

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.