Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

The continued

case for equities

The traditional risk-reward relationship associated with equities appears to have broken down – over the past three years, local equities have not rewarded investors for taking on the relatively higher risk of investing in this asset class. In fact, cash has outperformed equities over the period. Disillusioned investors are questioning whether shares are still a wise choice under the circumstances and some are looking to lower-risk asset classes to enhance overall returns. Is there a continued case for equities? Can we expect the risk-return trade-off investors rely on, to be re-established in the future?

The numbers certainly seem to justify investor angst. Since May 2015, the South African equity market has moved largely sideways and delivered lacklustre results – the total return for the market over the period was an unexciting 6.95% per year (dividends reinvested). Most economists continue to point the finger at the usual suspects behind this disappointing performance: the low-growth trap we seem unable to escape, exacerbated by poor macroeconomic policy making and execution.

While there are clearly legitimate reasons for the equity market’s disappointing returns, it should be remembered that when investors start to question a particular asset class, emotion – especially fear – is never far from the surface. In the face of short-term setbacks and uncertainty, people tend to lose faith in and ignore tried-and-tested long-term investment principles, thinking that ‘this time is different’. Jittery investors start overreacting and making decisions based on recent short-term experience at precisely the wrong time, which more often than not costs them dearly in the long run.

It’s human nature to get excited about short-term gains and losses on the stock market, and it’s sometimes difficult not to get caught up in the ‘noise’ and media hype impacting the market. As professional investment managers, we need to focus on the facts, however, and the most important is this: over the long term – and by this we mean at least 10 years – equities have significantly outperformed every other asset class. No one can deny that over the short term, local equities haven’t been shooting the lights out. But taking a longer term view, nothing trumps shares when it comes to inflation-beating returns.

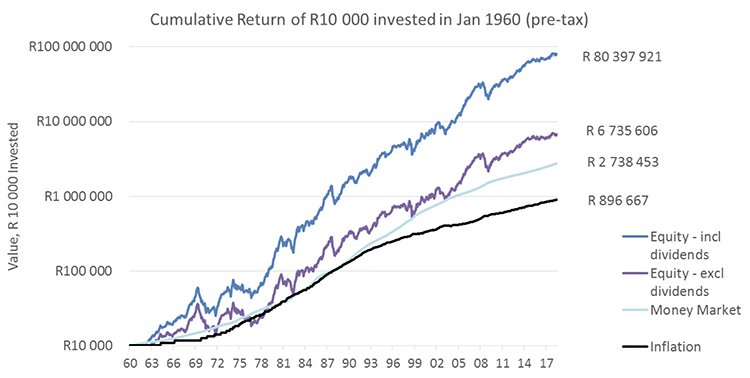

The facts speak for themselves: since 1960, there has never been a rolling five- or 10-year period in which equities delivered a negative return. In fact, the median return over five years since 1960 was 17%. A comparison between long-term equity returns, money market returns and inflation also illustrates the importance of equities. As can be seen on the graph below, an investment of R10 000 in 1960 in the money market would have returned R2.7 million at the end of 2017, while the equity market (dividends reinvested) would have delivered R80.4 million, a nominal return of 16.63% per year! Clearly, if you want to beat inflation over the long term, the equity market is the place to be.

Source: IRESS, SPW Research

This isn’t to say we should deny the reality of the short-term failures of the risk-reward relationship in our equity markets. Since 1960, there’ve been quite a few, most notably the 1998-2003 period, when investors became highly disillusioned with the five-year performance of stock markets. Similar to our current scenario, there were ‘good’ reasons then why the equity market disappointed for a sustained period: the emerging markets crisis in 1998, followed by the dot-com bubble and a slump in our currency.

Several ‘experts’ argued at the time that the conventional risk-reward relationship could no longer to be trusted, and many investors lost patience with equities. But those that did, paid dearly for their impetuousness – they lost out on what was subsequently the longest and strongest bull market in South African equities since the 1960s.

The problem with trying to time one’s participation in the equity market is that it normally happens after a period of underperformance, when equity prices tend to be cheaper. So from a valuation perspective, it’s absolutely the wrong time to be bailing out. Of course it’s important to allocate assets tactically at times, but jumping ship in rough seas when the vessel is unlikely to sink could have disastrous consequences.

How can we say for sure that our current equity market slumber is not different this time? There are of course no guarantees when it comes to investing – our safest course is to look at and learn from the patterns that have emerged over the years, and to remove emotion from our decision-making.

In our view, the crucial question isn’t whether investors should remain invested in equities or not – the focus should rather be on what will happen if they don’t. The fact is that missing out on the high-return months of our equity market over time can make an enormous difference to the long-term performance of an investor’s overall portfolio.

Generally, high-return months occur during the following three market phases:

We’ve isolated the top 40 months in terms of investment performance since 1960 (6% of the 702-month period under review). Missing out on the performance generated in this crucial but small proportion of the time would have resulted in an investor’s annualised return over the period dropping from 17% to 7% (R10 000 invested in 1960 would have returned only R710 000 at the end of 2017, compared to R80.4 million had an investor remained in the market for the 40 months in question).

Being out of the market during only the top 10 months would have led to returns falling from 17% to 13.5% (R10 000 invested in 1960 would have returned R20.15 million in 2017). So losing the opportunity of enjoying the gains of a relatively small percentage of the total months in the market can make a marked difference to an investment portfolio over the long term.

In the end, to achieve long-term investment goals, investors need to be patient enough to stay the course over time. The evidence suggests that investors seeking an inflation-beating investment outcome can’t allow themselves to miss out on the long-term rewards promised by equities as an asset class. The objective is always to beat inflation: maybe not this or even next year, but over the longer term. The only way to do this is by allocating a certain portion of assets, appropriate to each investor’s risk profile, to equity markets.

It’s worth noting that although the equity market may be risky over the short term, risk is significantly reduced if one takes a long-term view. As one remains invested in the market over longer periods, the volatility in possible returns reduces.

Investors considering leaving equities at this stage are ignoring the lessons of history – at their own peril. It’s not for nothing that the most expensive words in investing are ‘this time it’s different’.

Sanlam Private Wealth manages a comprehensive range of multi-asset (balanced) and equity portfolios across different risk categories.

Our team of world-class professionals can design a personalised offshore investment strategy to help diversify your portfolio.

Our customised Shariah portfolios combine our investment expertise with the wisdom of an independent Shariah board comprising senior Ulama.

We collaborate with third-party providers to offer collective investments, private equity, hedge funds and structured products.

Using your equity portfolio to secure credit allows you fast access to capital.

Sizwe Mkhwanazi has spent 14 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Sizwe?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.