Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

ELECTION 2024:

SA WILL 'MUDDLE THROUGH'

It has certainly been a fascinating two weeks since the South African national elections in late May. Although the final shape of a government of national unity is yet to be determined, we share our views on the situation as it is at the time of writing (12 June) and how we are approaching portfolio construction amid all the uncertainty.

To start with, it’s clear that many people, the team at Sanlam Private Wealth included, were surprised by the outcome of the recent national elections. Most people expected the ANC to fall to below 50% of the vote, with our estimate six weeks before the event at 46%, falling to 44% two weeks before voting day. The extent of the ANC’s decline – to only 40% – came as a surprise and was due to the performance of the MK party, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal, where it achieved 45% of the vote.

We warned back in April that if the ANC vote fell as low as it has, South African politics could get complicated, with the ANC required to form some sort of coalition. The reality we now face is that the ANC fell so far below 50% that constructing a simple coalition appears unworkable.

The original expectation that the ANC, IFP and perhaps one or two smaller parties could form a coalition government with the ANC clearly in charge is no longer possible. The ANC has to work with at least one of the DA, MK or EFF. Given that both the EFF and MK have their roots within the ANC, there is still a degree of ‘friendship’ between the members and the various officials in the parties.

At the same time, it appears that with the departure of the more radical elements of the ANC over the past decade, first to the EFF and then to MK, the remaining core of the ANC is more moderate. This is what President Cyril Ramaphosa is all about: building consensus through fairly moderate ideas. This level of moderation also means that apart from certain specific policy areas, the ANC is now, in general, closer to the DA than after previous elections.

With this new, more moderate ANC, we have an intriguing situation where, depending on how one defines ‘moderate’ or ‘centrist’ views, around 68% of South African voters are in this camp – the remaining 32% being more ‘radical’. Interestingly, there is scope for debate about whether MK and the PA might be classified as ‘left wing’ or ‘right wing’ given their nationalistic and conservative views on many subjects.

A few things stand out from the election statistics, the first of which is just how few South Africans bothered to cast their ballot. Given the intensity of the struggle for the right to vote in the 1980s and 1990s, this is a major disappointment. Voter turnout has been steadily declining since the 1990s, with only 59% of registered voters participating in the 2024 election compared to 89% in 1999, 77% in 2009 and 66% in 2019. But of even greater concern is the number of eligible voters who didn’t even register.

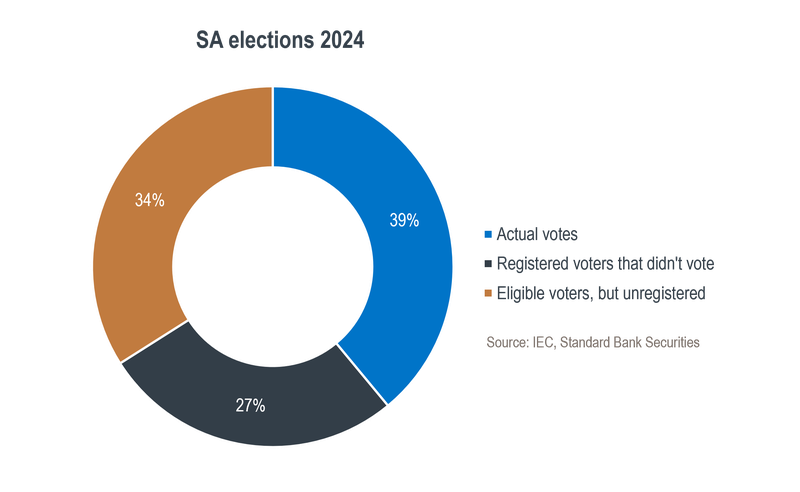

As illustrated on the chart below, of South Africa’s 42 million eligible voters, only 28 million were registered and of those, only 16 million went to the ballot box. We view this as a clear indication of the country’s broad disillusionment with democracy, which many people see as not working for them. Given the country’s struggles, disappointment is unsurprising, but what we find worrying is that rather than voting for a different party, over 60% of eligible voters just couldn’t be bothered.

It’s also interesting to note that voter turnout was the lowest in the areas in which the ANC fared the best – Limpopo, North West and the Eastern Cape all came in at below 55%, while KwaZulu-Natal, where MK did so well, was the highest at 62%.

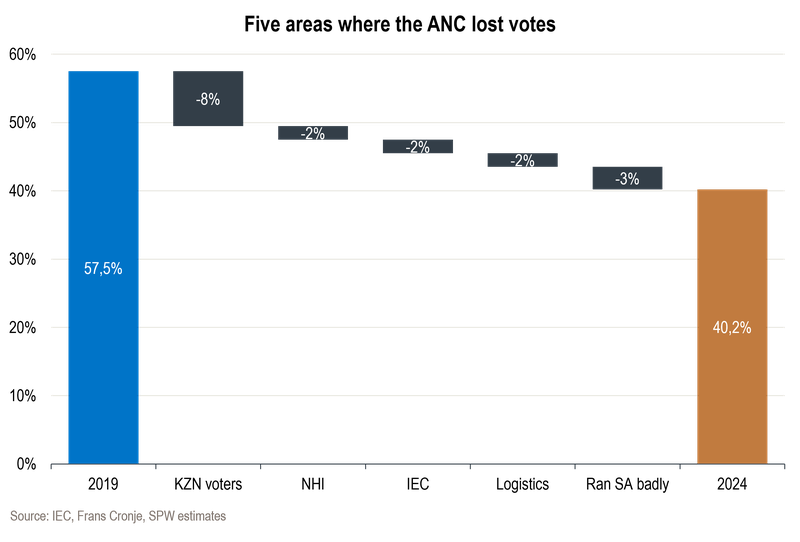

In conducting a post-mortem of the ANC’s performance, we absorbed the views of several commentators to come up with the estimates below of where the ANC’s 17 percentage point decline in votes came from. The largest portion is clearly the votes lost to MK, which we pin at around eight percentage points. However, we see around four percentage points as relating to the combination of the ANC’s own party logistics machine being less effective than previously at getting registered voters to cast their ballot on the day and the inefficiency of the Independent Electoral Commission of SA, which presided over long queues and poorly trained staff.

Public analyst Dr Frans Cronje made the point that the rushed signing of the National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill also appears to have backfired – he has suggested that this cost the ANC in the region of two percentage points. Both the current and aspirational middle-class voters see being denied the chance to use private healthcare as a negative.

As illustrated in the graph below, this leaves the final element – the poor running of South Africa over the decades since democracy – costing the ANC only around three percentage points in this election.

The limited impact of running the country badly on the ANC’s share of the vote certainly reflects poorly on the state of South African politics. This, together with the low voter turnout, suggests that South Africans in general aren’t inspired by the available options.

The ANC now wants to form a government of national unity (GNU) with representation by all the major parties. This appears to be an effective way of absolving themselves from blame by putting the ball in the other parties’ court and forcing them to state whether or not they’re willing to work with each other in a united government. Both the EFF and MK have indicated that they’re unwilling to work with the DA in a GNU. The DA appears willing to participate, as does the IFP, but we still see a small possibility that the EFF might change its stance.

We’ll learn more over the coming days, but for now, we’d like to point out that South Africa’s last GNU back in 1994 faced an uphill battle due to party differences, despite the leadership of former President Nelson Mandela. At that time, the NP and IFP accounted for 15% and 11% of the ministers respectively, on the back of 20% and 11% of the votes.

Should a GNU be formed by the ANC, DA and IFP, a potential outcome could be that of the probable 26 ministries, the ANC would take 20 (77%), the DA would get around five (19%) and the IFP one (4%). We view this as a reasonable outcome for the country from an economic perspective but note that such a GNU would likely struggle to be sustained over the full five years until the next election.

South African politics has entered a new era in which the fragmented nature of our country from both a race and class perspective means we will likely not see a single party garner more than 50% of the vote for many years. This means that our politicians will need to become proficient in the art of compromise. We view President Ramaphosa’s key skill as his ability to build consensus, which will surely be tested to the limit not just in the coming weeks but for years to come.

What are investors to make of the current political environment in South Africa while we wait for a GNU to be formed? Amid all the uncertainty, the value of an appropriately diversified portfolio cannot be overstated. A case in point is that over the seven trading days after the election, while the overall SA equity market fell by 2.2%, our SA equity portfolio declined by only 1.7%.

This highlights a key tenet of our investment philosophy at Sanlam Private Wealth: we look to construct our clients’ portfolios to be robust and resilient in the face of multiple macroeconomic outcomes. The positions we take are aimed at owning quality assets purchased at attractive prices. Our investment thinking is focused on the long term rather than on taking bets on short-term events that have both high uncertainty and high impact.

While both the short- and medium-term outlook for local politics and the impact this will have on our economy remain unpredictable, our base case remains that South Africa will ‘muddle through’, as we’ve done for decades. To quote former Prime Minister Jan Smuts: ‘In South Africa, the best never happens, and the worst never happens.’

Sanlam Private Wealth manages a comprehensive range of multi-asset (balanced) and equity portfolios across different risk categories.

Our team of world-class professionals can design a personalised offshore investment strategy to help diversify your portfolio.

Our customised Shariah portfolios combine our investment expertise with the wisdom of an independent Shariah board comprising senior Ulama.

We collaborate with third-party providers to offer collective investments, private equity, hedge funds and structured products.

When formulating your investment strategy, we focus on your specific needs, life stage and risk appetite.

Greg Stothart has spent 16 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Greg?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.