Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

Jack is back – business

as usual for Alibaba?

The ‘disappearance’ of Alibaba Group co-founder Jack Ma in October last year and the abrupt suspension of the much-anticipated initial public offering (IPO) of Ant Group amid a Chinese regulatory clampdown on internet firms sent Alibaba stocks plummeting. The tech billionaire has since resurfaced, investor relief being reflected in the internet giant’s share price. What are investors to make of all this – is it business as usual for Alibaba now, or is the Chinese regulatory pressure cause for concern?

Jack is back! Or so we think. Towards the end of January, the chattering classes were silenced by the return of Alibaba Group co-founder Jack Ma to the public limelight. It was a brief appearance, and he was discussing education rather than his beleaguered business empire, but it was enough to send shares in Alibaba north. He had not been seen in public for weeks and rumours about his whereabouts had veered between the absurd and the sinister. What to make of all this? Let’s first recap how we got to where we are.

In October, Jack Ma took to a Shanghai conference stage and criticised the Chinese regulator for being anachronistic and stifling innovation. He even went so far as to accuse the government of having a ‘pawnshop mentality’. Then, in November, the IPO of Ant Group (a third of which is owned by Alibaba), touted as being the largest in history, was torpedoed by the government.

Following this, Beijing put forward new proposals intended to curb monopolistic practices across the internet landscape. E-commerce was especially in the firing line with certain bad practices, such as exclusivity agreements and selling at below cost, being explicitly condemned. Then, just before Christmas, it was announced that Alibaba was being investigated by the government for monopolistic behaviour. This string of bad news caused the share price to fall from above US$300 to around the US$220 mark.

Should investors be concerned? The first thing to note is that Alibaba is more than just Jack Ma. Yes, he is the inspirational figurehead, and the father of Chinese tech entrepreneurism, but the company has moved on. He stepped down as CEO in 2013 and as chairman in 2018. He’s not even on the board any more. The current CEO is Daniel Zhang, a highly respected executive, and the creator of the largest shopping holiday in the world, Singles’ Day.

It’s also worth noting that an overly punished Alibaba probably doesn’t serve the needs of the Chinese Communist Party. Alibaba’s 20-year rise to supremacy is due in no small part to government policies, which protected and cultivated the internet sector. Under the guise of national security, we’ve seen foreign ownership restrictions that have stamped out competition from overseas. It seems unlikely that the government would go to all that trouble to then undermine what they had helped create.

China has for many years wanted to show that it’s a good country in which to do business. Completely undermining the country’s number one entrepreneur seems a poor way of trying to achieve this. In October, the government unveiled its economic plan for the next five years – technology is now a key area for China. Indeed, the new plan has elevated China’s self-reliance on technology into a national strategic pillar. Destroying one of your leading technology companies would be a counterproductive first step in this plan.

For these reasons we believe that the most likely course of action will be a public falling into line by Jack Ma, a few concessions in terms of e-commerce bad practices, and then business as usual for the company.

If we’re not too concerned with the current situation regarding its co-founder, what do we make of Alibaba’s long-term prospects? We believe that a positive view on the group is largely predicated on two things: gross merchandise value (GMV) growth and take rate expansion.

Looking at GMV, we like to split this into number of users and how much those users spend (in e-commerce parlance this is referred to as average revenue per user, or ARPU). As of 31 March 2020, Alibaba had 726 million annual active customers on its Chinese retail marketplaces, making the group the largest e-commerce platform in the world. We believe there’s still room for further user growth, but what is the ceiling? The first target, we believe, will be 900 million, as this is how many users Alipay has – we would expect this to be reached in the next three years or so.

Growth beyond this will primarily come from less developed areas of China, including lower-tier cities and rural areas. Alibaba has noted in the past that there is 85% penetration in developed areas, whereas in lower-tier cities and rural areas this drops to 40%. If in the long run user penetration was uniform in all of China at 85%, the Alibaba user base would be around 1.2 billion. This suggests a still large opportunity for user growth.

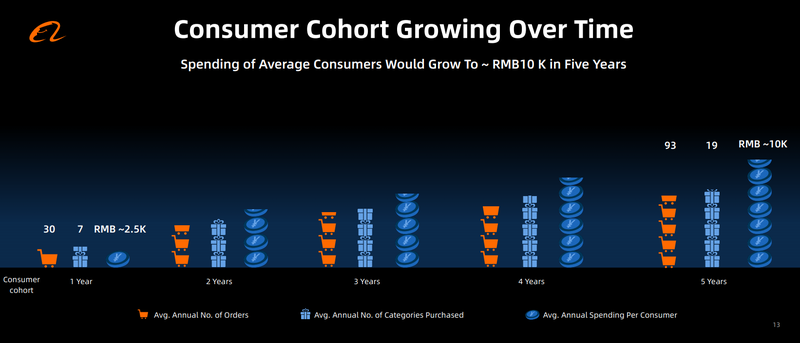

In terms of ARPU, the dynamics at Alibaba are very positive as increased spend occurs the more comfortable an individual user becomes with the platform over time. Alibaba has in the past revealed that the average user’s spending on its platform quadruples in the fifth year compared to the first (see graph below). As more customers join the platform and get used to using it, we can expect that user to spend more.

Source: Alibaba

Take rate expansion is another big opportunity for Alibaba. The take rate is defined as the revenue that Alibaba generates as a percentage of GMV. In fiscal 2020, Alibaba’s take rate was 3.8%. When compared to offline businesses, this is extremely low. Offline businesses usually pay significant rental costs – the Chinese average of rental costs as a percentage of sales is estimated to be in the 10-15% range. In Shanghai it’s towards the top end of this range, around 15%, and for Hong Kong, at some of the leading shopping malls, it’s around 24%. Eventually, we believe that online and offline businesses will reach an equilibrium where the cost structure is the same. The equivalent of rental for online operators will be commission and advertising. This suggests that over the long term, Alibaba’s take rate could easily be above 10%.

In a nutshell, we believe that the future of Alibaba looks promising, with or without the re-emergence of Jack Ma.

Note: Alibaba is a key holding in the Sanlam Global High Quality Fund.

Sanlam Private Wealth manages a comprehensive range of multi-asset (balanced) and equity portfolios across different risk categories.

Our team of world-class professionals can design a personalised offshore investment strategy to help diversify your portfolio.

Our customised Shariah portfolios combine our investment expertise with the wisdom of an independent Shariah board comprising senior Ulama.

We collaborate with third-party providers to offer collective investments, private equity, hedge funds and structured products.

We can help you maximise your returns through an integrated investment plan tailor-made for you.

Niel Laubscher has spent 10 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Niel?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.