Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

JUNK STATUS FOR SA:

NOT ALL DOOM AND GLOOM

The inevitable has now finally happened. In its latest sovereign credit rating review, Moody’s rating agency has downgraded South Africa to junk bond status – on the first day of a national lockdown in response to the escalating global COVID-19 pandemic. While our Finance Minister believes the downgrade couldn’t have come at a worse time, in our view, it may not be all doom and gloom. Some of the bad news may already have been priced in by financial markets, and the timing may not be as unfortunate as it appears at first glance.

South Africa’s economic growth pattern and fiscal woes associated with poor economic policy formulation and execution have since 2014 cast doubts over the country’s credit rating by the top three rating agencies: Standard & Poor’s (S&P), Moody’s and Fitch Group. The issue is certainly not unimportant – our credit rating has a direct impact on our ability to access foreign capital and crucially also on the cost of funding.

In December 2015, the level of government debt and low growth prospects for the local economy led to both Moody’s and S&P downgrading the outlook of our credit quality to ‘negative’. We stated at the time that muted revenue growth doesn’t usually allow for expansionary fiscal policy, let alone in an environment where government’s debt path is rapidly going in the wrong direction. The change in outlook by the agencies meant that the status of foreign-denominated South African debt was likely to be downgraded from low investment grade to non-investment grade – popularly known as junk bond status – if the country did not address its deteriorating fiscal position and below-par economic growth trajectory.

This indeed occurred in 2017 – both Fitch and S&P took us to junk status. Moody’s, however, held out – until Friday 27 March, when the inevitable happened and the agency downgraded South Africa’s sovereign credit rating to sub-investment grade from Baaa1 to Ba1. Finance Minister Tito Mboweni responded to the downgrade with a ‘heavy heart’: ‘The decision by Moody’s couldn’t have come at a worse time. South Africa, like many other countries, is seized with containing the outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19).’ At Sanlam Private Wealth, we’re not entirely convinced the timing is indeed inopportune – but more about this later.

It’s hard to find any positive outcomes for the South African economy resulting from this downgrade. As Minister Mboweni said: ‘To say we are concerned and trembling in our boots about what might be in coming months, is an understatement.’

A downgrade below investment grade means South Africa will now be excluded from all important global bond indices. We’re currently included in Citigroup’s World Government Bond Index (WGBI). The exclusion means that foreign investors who aren’t allowed to invest in sub-investment grade bonds and who are holders of South African bonds will be forced sellers of these instruments. Between US$5 billion and US$11 billion could be sold off.

If these sales materialise, one would logically expect that government bond prices will decline given the increased supply. In investment terminology, the yields will move higher and the cost of foreign funding for the government is likely to increase – at a time when sovereign debt is escalating given the financial woes of our stated-owned enterprises (SOEs), especially Eskom, and the fiscal burden associated with funding measures to fight the impact of COVID-19.

In short, it would add further pressure to an already dire local fiscal situation. Whatever scope there was to support monetary stimulus at a time when the local economy needs policy support, has now been further reduced. This is hardly what we need when the local unemployment rate is at unprecedented levels and social demands are increasing.

All things being equal, one would expect that the local currency will come under pressure, bond prices will decline, and the prices of local equity counters – particularly those of banks – will be impacted. We’ve argued in the past that this downgrade was inevitable, and if financial assets do discount very likely future events, one could argue that at least some of the news of this downgrade should already be priced into these assets.

However, to claim a particular future outcome at a time when investor psychology is extremely fragile as a result of the impact of COVID-19, would be either very brave, or very stupid. No one knows what lies around the corner – we can only make a call based on how similar events unfolded in the past, and how prices have recently performed.

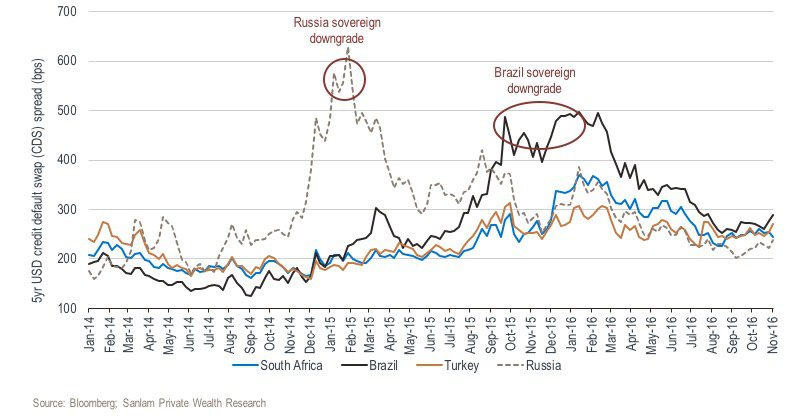

We should see the most direct impact of a lower credit rating in the cost of South Africa’s foreign- denominated debt. In 2016, we argued that our foreign credit was already regarded by investors as being sub-investment grade. The chart below shows a comparison of the cost to insure certain governments’ foreign currency debt (so-called credit default swap, or CDS) against default. It’s noteworthy that South Africa was already priced in line with other countries that were rated ‘junk’ by one or more rating agencies.

It can also be seen on this graph, however, that in an event of a downgrade, investors tend to respond in a knee-jerk fashion – such as when the price of ‘insurance’ of both Russia (February 2015) and to a lesser extent Brazil (September 2015) disconnected with that of their emerging market peers. In both cases, the prices later converged with the peer group.

The macro narrative of these two countries then was not dissimilar to that of South Africa now. And yet, their currencies remained relatively resilient at the time. The fact that the rand has already lost 20% against the US dollar (a safe-haven currency), and also gave up 9% against the Australian dollar over the past two weeks, would suggest that much of the uncertainty resulting from the downgrade as well as the impact of COVID-19 has already been priced into the currency.

South African bond prices have declined materially over the past month as the potentially negative impact of COVID-19 on our fiscal resources became a reality. Our 10-year government bond yields weakened from 8.86% on 3 March to an eye-watering 12.3% on 23 March. We doubt that this repricing had anything to do with the looming credit downgrade.

Given this extreme response, South Africa now has the highest yield of the 14 currencies in the WGBI. Despite the fact that we’ll fall out of the WGBI, South African credit is likely to hit the radar screens of investors seeking attractive yields in a low-yield investment universe. With regards to the currency, we’d argue that our bond yields would be attractive enough for some investors, and therefore one would expect a ceiling not materially higher than the current yields.

What about equity prices? COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on the markets – see our earlier article on the extent of the impact. Bank shares have been particularly weak – the Absa share price, for instance, has traded 48% down from its opening levels in January. Although the downgrade isn’t good news for the banks, their asset prices are reflecting doomsday scenarios. Should share prices fall further, we’d view this as a further disconnect between the true value and the market price of these assets.

In our view, the timing of the downgrade might not be quite as bad as the Minister has indicated. South Africa’s dire fiscal position, while we’re also caught in a (largely self-inflicted) low growth trap, is well-known. One option is to approach the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for funding to relieve pressure on the fiscus. Under normal circumstances, this won’t sit well with foreign investors looking for reputable investment opportunities. However, the outbreak of COVID-19 has highlighted the fragile fiscal positions of many other countries. Should we therefore now approach the IMF for funding, it’s not likely to draw the same attention that it would in ‘normal’ circumstances.

Minister Mboweni was quoted in the Sunday Times newspaper yesterday (29 March) as saying that South Africa could proceed to talk to the IMF and the World Bank about any facility that could be accessed for ‘health purposes’. In our view – and we might be a bit naïve – his remarks about ideology are noteworthy: ‘We take no ideological position in approaching the IMF or World Bank.’ As any funding from these institutions would be accompanied by clear conditions, it may provide the impetus for pragmatism with regard to the ANC’s economic policy – and its execution.

(Listen to Alwyn's views on the timing of the downgrade here.)

We are of course acutely aware of investor anxiety resulting from the decline in the values of their investment portfolios. It is even more traumatic for our retired clients, who need to live off the income generated by their portfolios.

When we manage our clients’ portfolios, we do so with the knowledge that we can’t forecast the future. What we do know is that on balance, when we accumulate assets of which the true value is materially higher than the market value, clients will reap the benefits through an investment cycle.

Of course, the duration of the cycle is often uncertain. However, as was the case during the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, our research would suggest that prices are now materially below their true values. Despite the downgrade and the immense uncertainty created by COVID-19, the prospective returns across a wide range of assets look more attractive now than at any time over the past five years.

Sanlam Private Wealth manages a comprehensive range of multi-asset (balanced) and equity portfolios across different risk categories.

Our team of world-class professionals can design a personalised offshore investment strategy to help diversify your portfolio.

Our customised Shariah portfolios combine our investment expertise with the wisdom of an independent Shariah board comprising senior Ulama.

We collaborate with third-party providers to offer collective investments, private equity, hedge funds and structured products.

We provide daily reporting of trades, monthly portfolio evaluations and annual tax reports to clients.

Riaan Gerber has spent 16 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Riaan?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.