Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

SA government bonds:

are they worth the risk?

The story of South African government bonds over the past 20-odd years is essentially one of two halves. While bond yields declined materially between 1999 and 2012, this trend was reversed in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (GFC), exacerbated by both the global economic environment and fiscal woes on the home front. Currently, yields on local government bonds appear attractive relative to history – but will investors be compensated for the risk of holding them in a multi-asset portfolio?

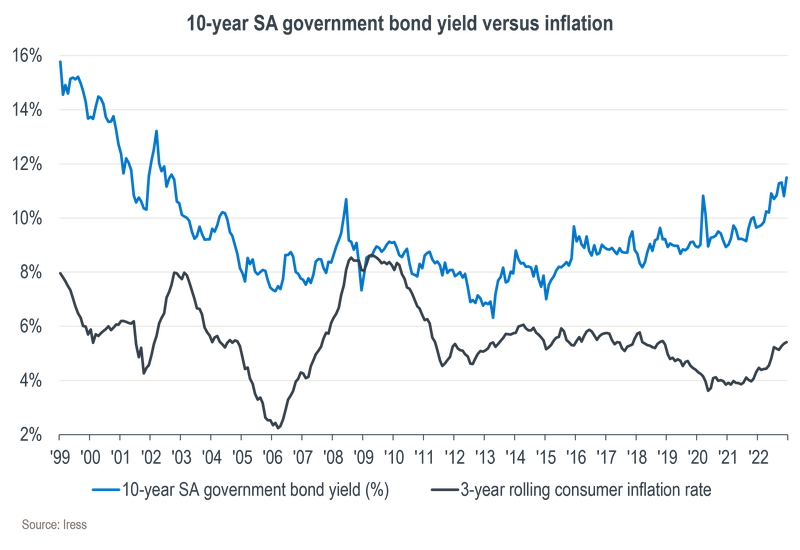

The chart below shows the yield on a 10-year South African government bond since 1999, and how this compares to the inflation trend:

The yield declined materially between 1999 and 2012, when the combination of higher commodity prices and prudent government policies during the Thabo Mbeki and Trevor Manuel era resulted in a structural decline in inflation and a material improvement in government finances. Bond prices move in a direction opposite to their yields, so South African bond investors received an attractive compounded return of 13.5% per annum over the period, well above the 5.6% average inflation rate.

However, the 2008/09 GFC marked a turning point in this state of affairs. While the healthy fiscal position at the time created room to justifiably support the local economy in a countercyclical fashion, a combination of lacklustre global growth, lower commodity prices and economic mismanagement under Jacob Zuma’s presidency resulted in a sharp deterioration in the state’s creditworthiness over the next decade. The economic restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic compounded the problem.

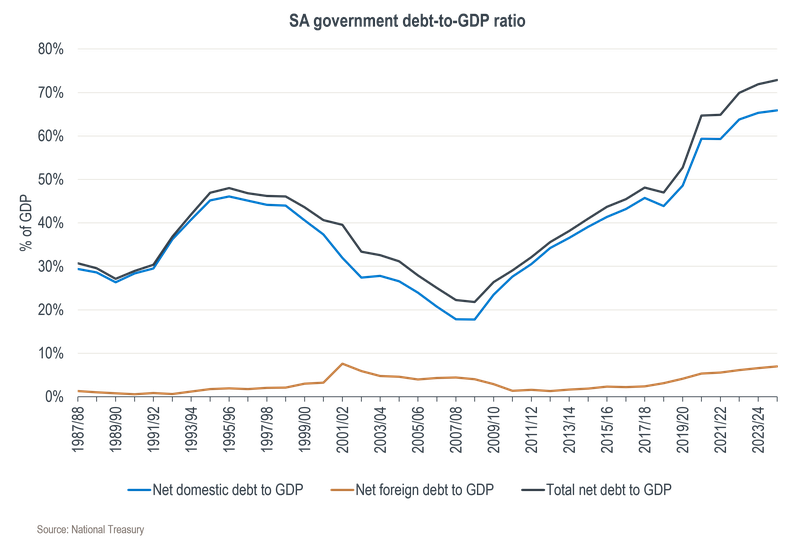

With tax revenue persistently falling short of budget and government expenses growing ahead of the economy, the government debt-to-GDP ratio ballooned from 22% in 2008 to a projected 70% at the end of the current fiscal year, as indicated on the chart below. This figure excludes another 15% of GDP worth of government guarantees and contingent liabilities through state-owned enterprises – mainly Eskom.

The state’s weaker financial position – confirmed by the multiple downgrades by credit agencies over the past decade – has resulted in bond investors requiring higher yields to compensate for the increased credit risk. More recently, the rising bond yields of developed nations have also put further upside pressure on South Africa’s bond yields in order to maintain their relative risk premium.

South Africa is now in danger of falling into a debt trap, where rising debt servicing costs are consuming an increasing portion of tax revenue, which could ultimately make it impossible to service the debt. The problem is compounded by the fact that South Africa is also running a current account deficit and has a low domestic savings rate, which means that we rely on foreign investment flows to fund the deficits (which again comes at a cost through the future income payments on these investments).

At least National Treasury seems to understand the problem at hand. The recent rise in commodity prices has resulted in a temporary windfall of tax revenue, which it has earmarked mainly for reducing the budget deficit.

Treasury is also pushing back hard against government workers’ wage demands. This is important given the fact that the wage bill has grown much faster than the economy over the past decade, with government workers on average earning 30% more than private sector workers, and South Africa’s government wage bill being in the top 15% of countries globally relative to the size of its economy. It remains, however, a politically challenging task. There is also normally a negative near-term impact on the economy when a government reins in its spending.

Fortunately, South Africa does have deep and well-developed financial markets, while only a small percentage of its debt is denominated in foreign currency. This reduces the likelihood of a sovereign default, as the government could potentially monetise the debt (i.e. it could print money) to repay it. However, this will likely be highly inflationary, eroding the real value for bond holders.

Ultimately, in our view, the only sustainable solution to avoid a so-called fiscal cliff is for the government to implement the necessary structural reforms that will improve the potential economic growth rate of the country. Key to this are the so-called network industries such as electricity and transport that need to become more competitive (and functional).

Given the constrained fiscal space and government capacity, South Africa has no other choice but to leverage private sector involvement and investment to rebuild these industries. Under President Cyril Ramaphosa’s reform agenda, there has been positive (but painfully slow) progress in this regard. There is, however, the obvious risk that it could be derailed by future political developments – a possibility that we must incorporate into our scenario analysis.

While the financial position of our government remains far from comfortable, one could argue that an investor is more than compensated for the risks by the high inflation-adjusted yields on government debt currently on offer. Also, if there is any improvement in the fiscal situation through a combination of better reform-driven economic growth, a sustained commodity bull market and prudent fiscal management, bond holders are likely to generate strong returns on their investments.

For example, if we assume that the 10-year bond moves back to our estimated fair yield of 9% in three years’ time, investors will earn a compounded return of 14.7% per annum over this period. But even if yields stay at the current elevated level, investors can expect a return of over 11%.

And while bond prices have been under pressure over the past year due to international factors, there have been green shoots from a fundamental point of view, including higher-than-budgeted tax revenue and an earlier peak in the debt-to-GDP ratio projected by Treasury. This was confirmed by rating agency S&P revising its credit rating outlook on South African government debt to ‘positive’ in April – a notable deviation from the trend in recent years.

At Sanlam Private Wealth, we assess the appropriate exposure to South African government bonds within a multi-asset portfolio by considering whether the prospective returns appear attractive relative to the perceived risk of the asset class. Whether or not the downside risks materialise depends on future developments that can’t be forecast with certainty. However, in our view, the near-term risk of a default remains low. One can try to manage the uncertainty through exposure to other assets expected to perform well in the event of an adverse outcome for local government bonds, resulting in a more resilient portfolio.

So, rather than taking unnecessary portfolio risk or missing out on the potentially attractive returns by completely avoiding it, we can use the benefits of portfolio diversification to manage the tail risk associated with each investment in the portfolio, including South African government bonds. While the higher yields against the backdrop of marginally improving fundamental factors over the short term justify their holding in our multi-asset portfolios, we will continue to take an active approach and reassess the risks against the fiscal signposts along the way.

We’ve recently expanded our direct bond offering at Sanlam Private Wealth, which will allow clients to capitalise on the attractive yields and allow us to better tailor portfolios for individual income needs. If you’d like more information, please don’t hesitate to contact your portfolio manager.

Sanlam Private Wealth manages a comprehensive range of multi-asset (balanced) and equity portfolios across different risk categories.

Our team of world-class professionals can design a personalised offshore investment strategy to help diversify your portfolio.

Our customised Shariah portfolios combine our investment expertise with the wisdom of an independent Shariah board comprising senior Ulama.

We collaborate with third-party providers to offer collective investments, private equity, hedge funds and structured products.

We can help you maximise your returns through an integrated investment plan tailor-made for you.

Niel Laubscher has spent 10 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Niel?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.