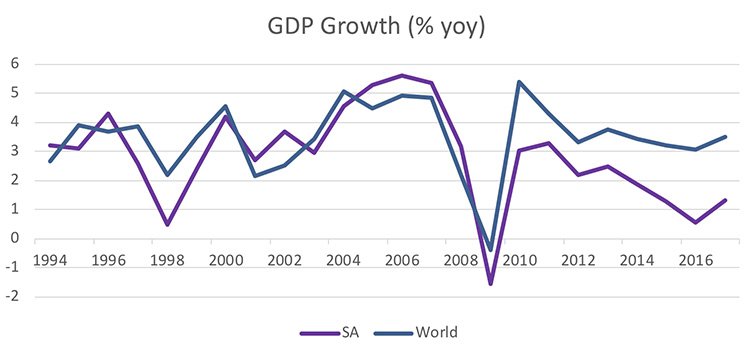

In global context, South Africa has a small, open economy, which means we’re very much exposed to what happens in the world economy. The chart below illustrates this clearly. Since our democratic transition in 1994, South Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate has been closely linked to global growth:

Source: SPW research

However, what’s also evident is that in the latter years of the Zuma presidency, our local economy started to diverge from the global trend. This is at least partly the result of poor macro-economic management. The Ramaphosa election led to renewed enthusiasm for the possible reversion of this trend – but five months into the new presidency it’s worth evaluating whether we’re heading in the right direction.

SO WHAT’S NEW?

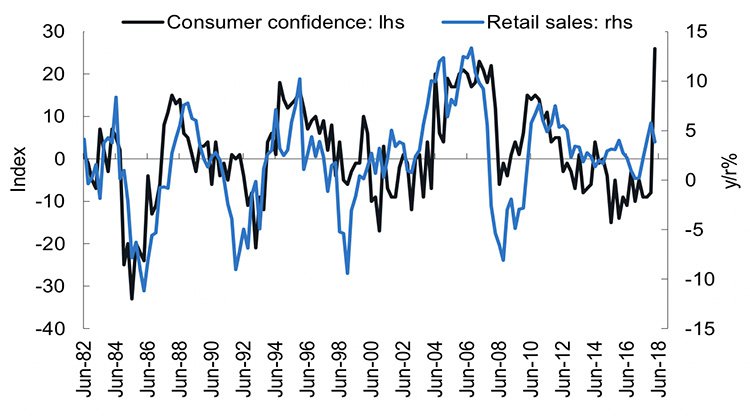

Despite the initial euphoria, South African consumers are still under pressure. The graph below illustrates the disconnect between consumer sentiment (left-hand side) and actual retail sales growth (right-hand side). Despite a marked increase in confidence, the retail sales growth rate declined:

Source: SPW research

Further tax increases have resulted in personal income tax rates reaching their highest levels in recent history, and given our precarious fiscal situation, they’re not expected to come down soon. In addition, the recent increase in the oil price to highs last seen in 2014 means fuel prices have also gone up, further reducing consumers’ spending power.

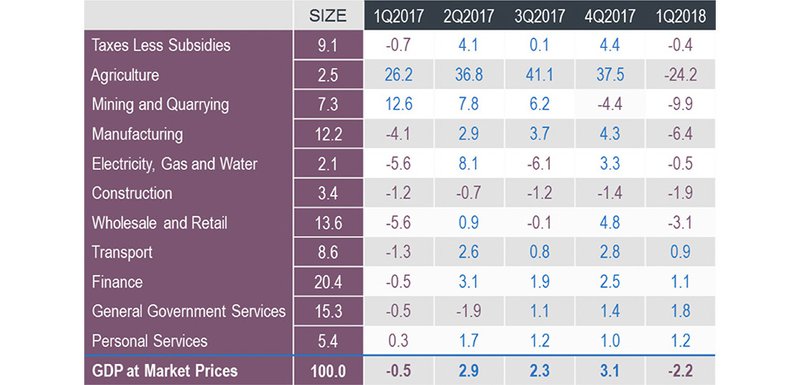

The growth numbers of the first quarter – in fact, we can hardly call it ‘growth’, since the size of our economy shrunk – were below expectations. There was an overall decline of 2.2% compared to the previous quarter, the main detractors being the mining, agriculture, manufacturing, and wholesale and retail sectors, as can be seen in the table:

Source: SPW research

WHAT LIES AHEAD?

Looking at the less-than-rosy picture in the major sectors of our economy, one wonders where economic growth will come from. Mining and agriculture have declined in importance in recent decades and are unlikely to be a major source of growth. Manufacturing has struggled to compete with China effectively and hasn’t contributed meaningfully over the past 10 years, and we don’t see this trend changing soon. Pessimistic local consumers are also unlikely to assist in boosting growth, at least in the near term.

Government’s contribution increased under the Zuma administration primarily due to above-inflation wage hikes. However, as became clear in the February Budget Speech, government is constrained in its ability to spend more. In addition, our state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are still in deep financial trouble – the state of affairs at Eskom being a primary concern. Government is therefore unlikely to be a major source of growth soon.

We’re concerned about the near-term outlook for the South African economy. Unlike many economists, we’re of the view that it will be a tough ask to increase growth to 1.5% in 2018. Although we do believe that our new president is serious about getting the economy back on track, reality suggests that he faces a more daunting task than initially thought, and we need to hold on for what’s likely to be a long, uphill climb.