Everyone likes a sweet treat, even adventurous bikers living the dream of open roads and scorching-hot metal. This must have been Harley-Davidson’s thinking when it licensed the brand to a cake-decorating kit.

Unfortunately for Harley, the Hell’s Angels passed on bake-offs, and the misfired branding exercise has become a classic example of how not to do it. Harley has now much more successfully licensed brand extensions such as clothing and sunglasses.

By stretching their brands, companies can leverage equity and spend efficiency and speed consumer adoption, says Dita Kreschel, CEO of Direct Action, The Brand Building Company. Earth-moving manufacturer Caterpillar, for instance, extended into fashion by licensing its brand to footwear.

‘Caterpillar brand stretching is a classic example of a team that clearly understood what the brand stood for, which enabled it to extend into gifts and apparel with the same rugged, outdoor, built-to-last image,’ Kreschel says. Brand extension also reduces business complexity. ‘It’s in keeping with most multinationals’ desire to have fewer, bigger brands aligned with the concept of master brands and global brands,’ she says.

DRIVING FORCE

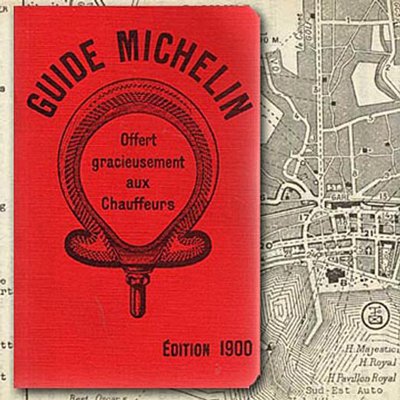

In a tough consumer landscape, many companies now look for ways to squeeze more from their label, but sometimes it happens by accident. One of the oldest examples is Michelin, the French tyre company. At the dawn of the motoring age, Michelin wanted to encourage nervous French drivers get out of Paris

Lack of fuel stations meant there was a high risk of getting stranded, so they produced a guide to where drivers could fill up. Being French, it also recommended a good spot for lunch. Today, the Michelin Guide is the gold standard for culinary enthusiasts.

Sometimes a pairing up is just an obvious good idea. US coffee chain Starbucks has always been more about the experience of coffee drinking than the coffee itself, Kreschel explains. ‘A deep understanding of its consumers led Starbucks to the insight that it is all about the social experience. Hence, Starbucks partnered with book stores and also launched its own compilation CDs.’

Or how about Italian fashion brand Gucci? In an attempt to reach out to shoppers even further and expand beyond its core but saturated fashion businesses, in 2015 it opened a fine dining restaurant, 1921 Gucci, in Shanghai. The aim was, reportedly, to ‘enhance its customers’ intrinsic aspirations’.

Another established luxury fashion label with a culinary arm is Armani. Founder Giorgio Armani made his first foray into the world of food and beverage in 1989 and the brand now has restaurants and bars in key fashion cities, including Tokyo, Milan and Dubai. In Hong Kong, there’s the restaurant Armani/Aqua as well as the Armani/Privé bar and club, which boasts stunning views of Central from its rooftop terrace. The brand also has a premium chocolate line.

VIRGIN TERRITORY

For some businesses, brand extensions have ensured their survival. The Virgin brand would likely be stone dead now if it had stuck to being a music store. Today its jaunty red logo is found on gyms, an airline and even wine.

Brand extension can also be a cheeky way to get into an industry where someone else has already done the hard work. Cigarette maker Dunhill has begun producing a range of luxury pens, a concept pioneered by Mont Blanc.

‘It’s stealing a bit of a market from competitors who have already come to embody a particular sector,’ says Monalisa Molefe, managing director of the Artform Factory brand and marketing. ‘The work has already been done and the space is available for a clever competitor.’

Ultimately, if a brand extension is to succeed, it needs to meet three criteria: the brand should be a logical fit with the parent brand; the parent brand should give the extension an edge in the new category; and the extension should have the potential to generate significant sales.

And if the likes of Aston Martin, Ferrari, Mercedes-Benz, Omega, Ralph Lauren, Armani and Gucci – which have respectively branched out into condominiums, branded apparel, yachts and helicopters, high-end sunglasses and restaurants — think it’s a good idea, then surely it must be so.

SANLAM PRIVATE WEALTH INSIGHT

Brands provide a promise to the customer, generally related to quality relative to similar products. Take, for example, the shopper who picks Koo baked beans as opposed to a lower-priced store brand on the basis of perceived quality. This means the product can be sold for a higher price and supports volumes, providing a protective moat against competition, as a brand cannot be copied the way a product can.

As one moves to higher-value items, the value in the brand morphs to become a symbol of lifestyle, for example, Harley-Davidson, and/or exclusivity when you’re talking about brands such as Cartier, Louis Vuitton or Patek Philippe. The customer’s preference becomes based more on the brand than the product itself.

This facilitates higher profit margins, which are sustainable as long as the brand maintains or improves its position. Companies with top-end brands are typically less sensitive to the economic cycle and, accordingly, trade at higher valuations relative to peers with weaker brands.

From an investment perspective, the key is to identify where brand equity is growing – for example, the high fashion and luxury goods manufacturer Hermès, or declining, as in the case of alternative lifestyle brand Ed Hardy – and to position one’s portfolio accordingly.