Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

The art

of the matter

Not long ago, the word ‘investment’ used to be taboo in the art world, and in the investment world ‘art’ was something you bumped into on your way to a meeting. Today, art is increasingly viewed as an asset class in its own right in a well-diversified portfolio – the most recent trend being ‘art funds’ that promise attractive returns to investors. While art can be an excellent alternative investment if approached correctly, there are many pitfalls and it’s crucial to be well informed about the vagaries of the art market before rushing into a purchase.

William Kentridge (1955- ), Landscape, charcoal and pastel on paper

In recent years, the buying and selling of art has become a public spectacle. Sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s in New York and London have become the stage for the gavel to come down on record-breaking prices for a Picasso, Warhol or Basquiat – three of the 26 artists that attract up to 90% of all money spent on contemporary art at auction houses worldwide.

The sometimes eye-watering prices paid for top-quality artworks in recent years have caught the eye of investment professionals, who have been quick to develop all sorts of packages to sell a share in the growing market of art investment, some in the form of art funds. Although there are no publicly traded art funds in South Africa as yet, we’ve become fertile ground for the marketing of European and American art funds to those looking for alternative investments offshore.

Over the past 10 years, few art funds have achieved the necessary critical mass to make them viable for investors, however. Those that have survived the past decade have produced adequate to very good returns, but this seems to be the exception rather than the rule.

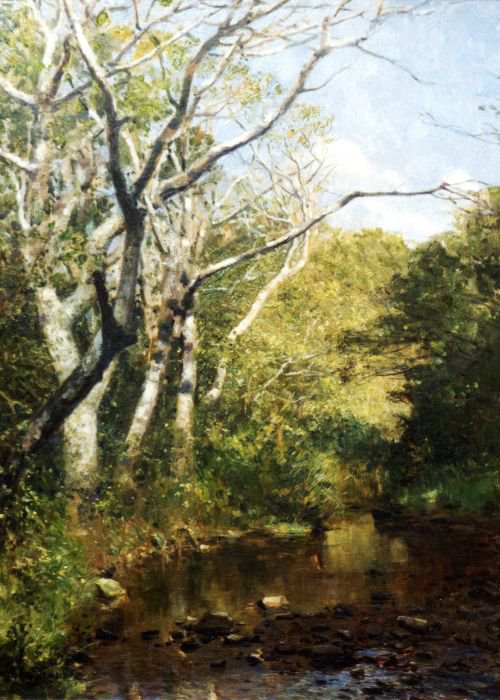

Cecil Thornley Stewart (1881-1967), Landscape with Stream, oil on board

In general, like any other asset class, art it has its complexities and peculiarities, and it’s not easily comparable to the tried and tested asset classes that usually populate an investment portfolio. There are many pitfalls and risks that investors need to recognise and manage.

From the outside, the art world, its products and its protagonists – artists, dealers, auctioneers and critics – look and sound arcane. Getting to know it well may require a long apprenticeship if you’re doing it on your own. Alternatively, you can obtain expert independent advice – this may come at a price, but the reward can be considerable.

It’s important to remember that unlike other markets, the art market is unregulated. There is no transparent pricing mechanism, such as a stock exchange. Anyone can open a gallery, an auction house or a museum. Anyone can present themselves as an expert, curator or critic. Such conditions make for an exciting playground for passionate, informed collectors, avaricious dealers, speculators and of course, scoundrels.

There are benchmarks of credibility, however, which are primarily associated with experience. Even a doctorate in a specialised area of art history won’t necessarily equip one with insights into the value of an artwork in the present market. With regard to dealerships, being in the art world for 20 years and still trading is a benchmark not easily achieved and retained.

Differentiating between the primary (debut sale of artworks) and the secondary (resale of debut works) markets in South Africa is instructive. The primary market has been alive and well for the past decade – there is no doubt our country is producing exceptional artists.

Some are already veterans, such as William Kentridge, Kendell Geers, Penny Siopis, Willem Boshoff, Sam Nhlengethwa, Diane Victor, Kay Hassan and Joachim Schönfeldt. Although well represented in the primary market through reputable galleries, works by these artists are now also finding their way onto the secondary market, confirming their longer-term value and ‘investability’.

A younger generation – Mary Sibande, Mohau Modisakeng, Igshaan Adams, Dan Halter, Nicholas Hlobo and Simphiwe Nzube, to name a few – is now emerging. It remains to be seen whether these artists will stand the test of time.

The pleasure of investing in the primary market lies in the diversity of choice, and is enhanced when the works of these artists receive recognition within the secondary market and the prices match or better those in the current primary market. This does carry significant risk however, especially when the ‘bright young thing’ you bought at a supposedly bargain price turns out to be a shooting star who has burned brightly, but only briefly.

The secondary market – often referred to as the ‘old masters’ market – is a very different playground. Until the turn of the century a handful of well-established galleries dominated this market, but today auction houses have taken over. Sellers of top-quality works by historically validated and celebrated artists prefer consigning these works to an auction house, as both national and international reach via the internet increases the number of potential buyers exponentially.

For buyers, the auction process appears to be the most transparent way to establish a market-related price for an artwork. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the price is fair, as anyone who has witnessed what two desperate bidders can get up to at an auction, will testify.

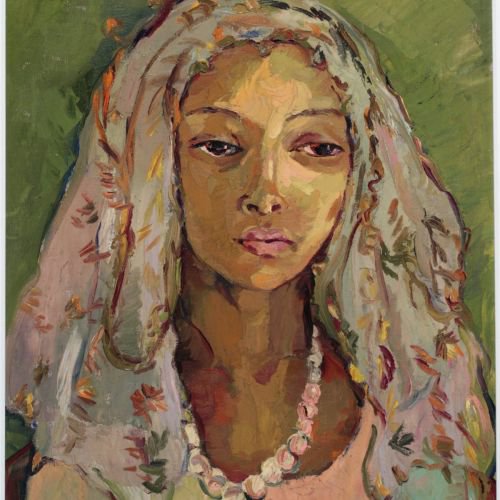

Irma Stern (1894-1966), Portrait of a Young Malay Girl, oil on canvas

Overall, the South African art market is healthy. For the inexperienced and uninformed however, it can prove to be a hazardous jungle dressed up as a manicured garden. It may be very difficult to see which of the two you’re wandering into.

For example, the priciest painting sold by a gallery in South Africa in 1966 was a painting by Cecil Thornley Stewart – but this is a name only a few art world veterans can recall today. By contrast, a portrait by Irma Stern purchased for the Sanlam Art Collection in 1968 for R1 260 could easily fetch R15 000 000 on auction today. It took some 48 years to get there though, and one must take into account that probably 98% of the increase in value occurred over the past 10 years.

In conclusion, buying art as an investment can be a highly rewarding and enriching experience. Good quality artworks will continue to engage way beyond the time of manufacture. Poor works, however, tend to rarely survive the euphoria of their original manufacture. Knowing the difference is key.

We provide daily reporting of trades, monthly portfolio evaluations and annual tax reports to clients.

Riaan Gerber has spent 16 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Riaan?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.