Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

Does your brand

have a conscience?

Gone are the days of paying lip service to sustainability. With a new breed of conscious consumer seeking ‘clean-label’ luxury, brands now face the kind of scrutiny that demands true innovation.

An East African coffee farm run along Fair Trade principles. Millennial consumers are more likely to buy from brands with ‘strong management of environmental and social issues’.

In a country with one of the world’s highest rates of inequality, ‘ethical luxury’ may sound like an oxymoron. On closer inspection, however, sustainability and luxury share key traits: they’re both concerned with the origin of raw materials and with craft – how these raw materials are shaped into a finished product.

What’s more, a new breed of ‘luxurians’ care more about using their spending power for good than they do about rarity, exclusivity and bling.

A Vivienne Westwood design made in accordance with ethical fashion principles.

This is according to ‘2016 Predictions for the Luxury Industry: Sustainability and Innovation’, a report published by Positive Luxury, a London-based company that screens and endorses luxury brands based on their commitment to ethical labour practices and earth-friendly manufacturing.

The report points to that oft-mocked generation, millennials, an influential section of whom now have access to considerable disposable income and who – despite their reputation for narcissism – are twice as likely to buy from brands with ‘strong management of environmental and social issues’.

Jeremy Nel, co-owner of Cape Town-based marketing agency Luxury Brands, agrees that high net worth millennials are leading the conscious luxury movement. ‘They’re determining a new horizon with regard to luxury goods, as opposed to inherited luxury based on old-school principles.’

Although Nel believes that the South African luxury goods market is still in its ‘evolution phase’, he sees this generation’s purposeful consumption spilling over into the mature sector of the luxury brand market as it comes of age.

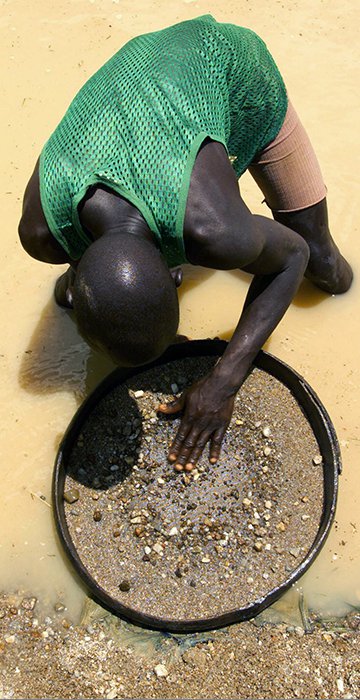

For Thebe Ikalafeng, founder of brand and reputation advisory firm Brand Leadership Group, the rise of the thoughtful luxurian is part of a much broader, continent-wide trend of self-awareness – ‘an awakening to the beauty and luxury of Africa’.

He points to a particularly African incarnation of the conscious consumer who demands impeccable environmental and labour practices while also looking to brands to take on a kind of socio-cultural responsibility.

‘Brands like Balenciaga, Louis Vuitton and Burberry have in recent years drawn heavily on African colours, beading and graphics,’ Ikalafeng explains. ‘These instances have magnified African design and so, combined with a growing pride in African identity, we’re seeing African consumers insist that luxury brands tell our stories.’

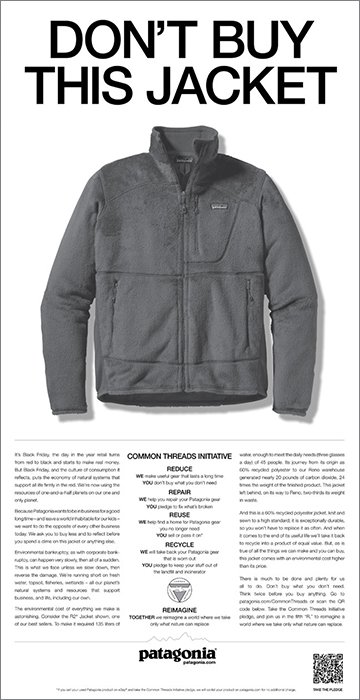

Internationally, US brand Patagonia has long led the way in steering the clothing industry in an authentically cleaner direction.

The company has donated 1% of its annual turnover to environmental charities and grassroots organisations for over 30 years, as well as founding the Sustainable Clothing Coalition. Some 30% of Patagonia’s product offering is also Fair Trade compliant.

Perhaps the most radical example of Patagonia’s commitment to ethical consumption was a series of adverts with the payoff line ‘Don’t buy our jackets’, placed to coincide with the annual consumer frenzy that is Black Friday.

In these ads, it pleaded with consumers not to buy more products than they really needed. Because the campaign was an extension of the brand’s long track record – including a policy of accepting returns on old goods, which it undertakes to recondition or recycle in exchange for store credit – it was seen as credible rather than as a cynical greenwashing gimmick.

As the demand for clean brands grows, so too does the potential for disingenuous marketing ploys. The new luxurian is demanding ever-higher standards of transparency, however, which means brands are also increasingly subject to legal obligations.

In 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals, a set of 17 goals ranging from gender equality to zero hunger by the year 2030, as well as the Paris Agreement, the climate change resolutions born of COP21, saw governments agreeing to adopt policies and implement laws that mandate environmentally and socially responsible production.

Also in 2015, the UK Parliament passed the Modern Slavery Act to hold big business more accountable for ensuring labour practices throughout the supply chain are ethical.

Asked how the concept of ethical luxury plays out in the South African luxury car industry, Jeanette Clark, Corporate Affairs Manager: Marketing and Sales for Mercedes-Benz South Africa, highlights parent company Daimler AG’s 2015 Sustainability Report, which explicitly references both the Sustainable Development Goals and the UN Global Compact – another initiative to encourage businesses worldwide to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies.

So the flurry of agreements drawn up in 2015 does seem to increase pressure on brands to behave honourably but ultimately, says Ikalafeng, it’s still up to conscious consumers to bring them to book, to verify claims and to insist on seeing the factories in which their luxuries are made.

Since all brands rely for their longevity on the availability of limited resources and materials, it certainly serves them well to step up of their own accord. As former UN Chief Ban Ki-moon said, ‘There’s no Plan B because there’s no Planet B’.

History is littered with the corpses of companies whose ethical standards slipped. Quite aside from the obvious brand damage and consequent cost of resurrecting trust in the brand through restorative PR campaigns, unethical business models are often the brainchild of fundamentally bad management – the type who cut corners and avoid addressing serious issues.

The world has moved away from the clichéd view that deception and bad practice is commonplace in the working world, and dismissed as ‘just business’. Similarly, the old adage of ‘caveat emptor’ is rapidly dropping out of the consumer vernacular, as a new wave of businesses like PayPal and Uber put unprecedented power in the hands of end customers.

Integrity as a value proposition

Companies need to live and breathe a value proposition which shows integrity as well as utility, or they will surely not succeed. Consumers rightly demand that managers of companies, who have a disproportionate impact upon the livelihoods of others, should as a bare minimum not worsen the world’s social problems.

In fact, managers are now expected to use their clout to actively contribute to sum of efforts to resolve social issues, and we see this trend continuing unabated.

Duncan Burden, Equity Analyst SPW UK

Using your equity portfolio to secure credit allows you fast access to capital.

Sizwe Mkhwanazi has spent 14 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Sizwe?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.