Stay abreast of COVID-19 information and developments here

Provided by the South African National Department of Health

Shoprite: a falling knife,

or food for thought?

After 14 years of uninterrupted growth, retail giant Shoprite stunned investors when, between the 2017 and 2019 financial years, its profits declined by nearly 40% in total. Whereas poor cash-flow conversion, a high valuation and currency concerns have kept us from owning Shoprite in the recent past, the sharp decline in the share price has reignited our interest in the company. In our view, most of Shoprite’s current challenges are temporary in nature and the retailer should be able to recover profitability going forward.

South Africa’s grocery retail industry has been characterised by healthy competition for a number of decades. This has been to the benefit of consumers, as retailers have had to work hard to provide a combination of low prices, range and convenience to meet the increasing demands of consumers. While Pick n Pay, with its philosophy of ‘consumer sovereignty’, pioneered modern grocery retail in South Africa in the 1970s and ’80s under Raymond Ackerman, it was Shoprite – under the leadership of Whitey Basson – that led the second phase of modernisation in the sector over the past two decades.

Shoprite’s success was driven by long-term investment into its centralised supply chain. This means stores are replenished via the company’s distribution centres, instead of directly by suppliers. The benefits of a centralised supply chain include better control over in-store stock availability, the ability to maintain a wider range of stock and supplier base, tactical buying and storage of stock ahead of price increases, and store cost savings as less space and fewer staff are required to receive deliveries.

While the centralised supply chain has provided Shoprite with an operational edge, the group has also positioned its trading brands well to compete in different target markets across income groups, and has expanded into the rest of Africa, where the penetration of formal retail is still low.

In addition to strong gains in market share in South Africa and growth in the rest of the continent, Shoprite managed to improve its trading profit margin from around 1% in 2000 to nearly 6% by 2017. This margin was well above that of competitors, despite the retailer carrying the lowest price perception among consumers – a clear sign of the operational supremacy it attained.

Over this period, Shoprite’s share price outperformed the FTSE/JSE All Share Index by 10% per annum. The better profitability enabled Shoprite to continue reinvesting higher amounts of capital into the business than its competitors to achieve further growth and more efficient operations.

However, things took a remarkable turn for the worse when, following 14 years of continuous growth, Shoprite’s profit fell nearly 40% in total between 2017 and 2019, as can be seen on the graph below. The share price lost nearly 60% of its value between March 2018 and August 2019.

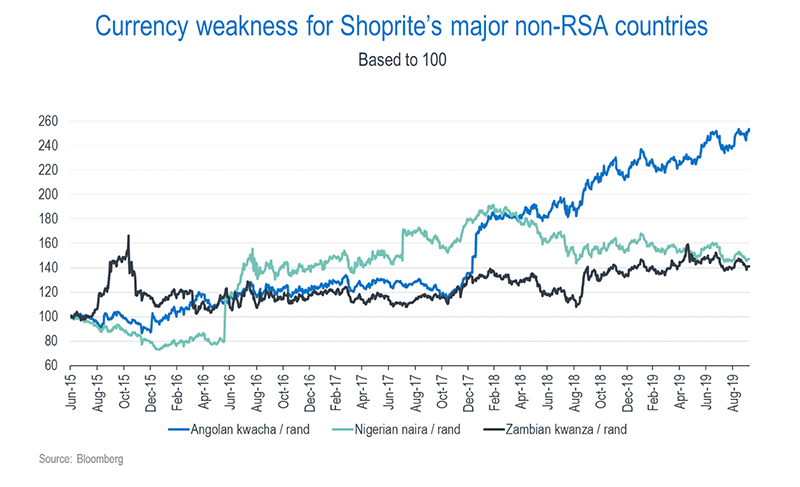

The biggest impact on profits came from foreign currency shortages and sharp declines in the value of Angolan, Nigerian and Zambian currencies – key markets for Shoprite (see the graph below). Not only did this negatively impact the rate at which earnings were translated into rand, but it forced price increases in these countries, which consumers struggled to absorb. While sales came under pressure, the high fixed cost of the store base continued, resulting in the non-South African supermarkets’ trading profit falling from R1.4 billion in 2017 to a loss of R0.3 billion in 2019.

The foreign currency issue is certainly a risk that we’ve flagged in the past when assessing the investment case for Shoprite. There was a large disconnect between the official exchange rates of Angola and Nigeria, where limited liquidity was available, and their parallel or illegal currency markets. Before the recent currency declines, Shoprite’s use of the official exchange rates to translate earnings therefore overstated the economic realities and rates at which cash was likely to be repatriated to South Africa.

While Shoprite’s growth engine in the rest of Africa had suddenly turned into a problem child, the South African operations, which still account for more than 80% of turnover, experienced their own pressures:

Despite the challenging period that Shoprite has gone through, we still believe the retailer’s business model, which focuses on improving the shelf prices of food for consumers through consistently improving the supply chain, has created a long-term sustainable business. Africa’s growing population will need food and Shoprite has an unmatched footprint across 15 African countries, supported by a world-class supply chain and technology systems.

Despite the sharp fall in the share price, Shoprite is still trading on 20 times normalised earnings. However, we believe that the earnings base is currently depressed, given the rest-of-Africa losses and challenges set out above. Shoprite’s investment case therefore rests on its ability to recover profitability, which is not without risk, given the group’s high fixed cost base and uncertainty over top-line growth in the current environment.

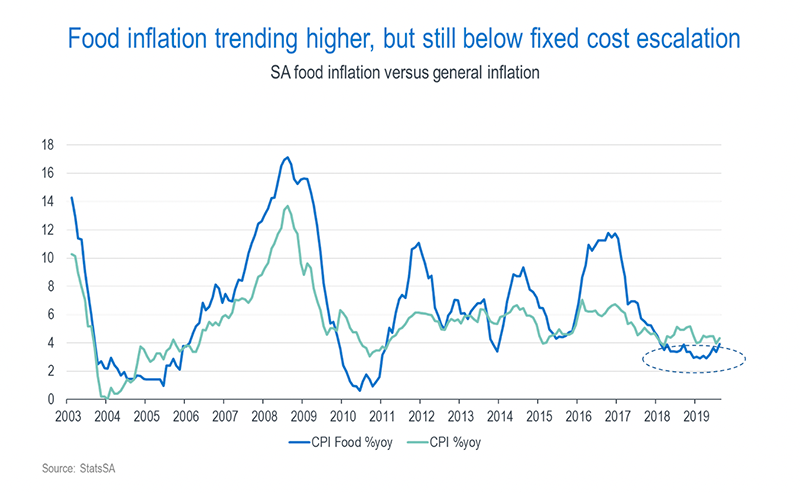

In our view, most of Shoprite’s current issues are temporary in nature, and therefore present an opportunity to buy a company that we’ve considered to be too expensive in the recent past. We’ve already started to see the South African sales volumes improve post-Shoprite’s distribution centre disruptions and food inflation ticking up slowly. The Angolan operations may take time to restore profitability, but at least much of the weakness is already in the numbers.

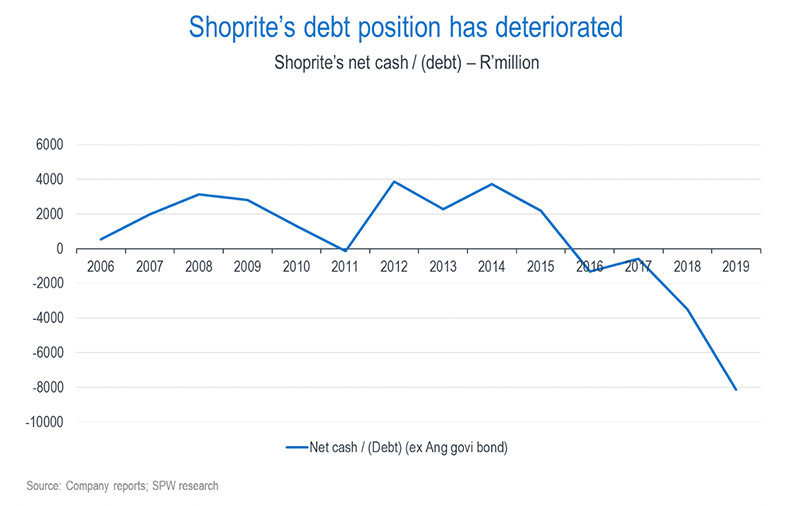

While the low cash-flow conversion has detracted from Shoprite’s investment case in the past, we do get the benefit of a business that has invested well in its infrastructure and technology, which it should be able to leverage in the future. We also believe management has a number of levers at its disposal to improve cash flow over the shorter term.

With its leading market share – in excess of 30% of grocery retail in South Africa – Shoprite’s fortunes remain linked to those of local consumers. While there’s undoubtedly still great pressure on South African consumers, we do expect a declining interest rate cycle to start providing some support for the sector, as we stated in a recent article. Consequently, and considering the fact that we’ve (correctly) maintained a relatively low exposure to domestic companies in our house view portfolio in recent years, we believe it’s an appropriate time to starting adding Shoprite to the portfolio.

Sanlam Private Wealth manages a comprehensive range of multi-asset (balanced) and equity portfolios across different risk categories.

Our team of world-class professionals can design a personalised offshore investment strategy to help diversify your portfolio.

Our customised Shariah portfolios combine our investment expertise with the wisdom of an independent Shariah board comprising senior Ulama.

We collaborate with third-party providers to offer collective investments, private equity, hedge funds and structured products.

Using your equity portfolio to secure credit allows you fast access to capital.

Sizwe Mkhwanazi has spent 14 years in Investment Management.

Have a question for Sizwe?

South Africa

South Africa Home Sanlam Investments Sanlam Private Wealth Glacier by Sanlam Sanlam BlueStarRest of Africa

Sanlam Namibia Sanlam Mozambique Sanlam Tanzania Sanlam Uganda Sanlam Swaziland Sanlam Kenya Sanlam Zambia Sanlam Private Wealth MauritiusGlobal

Global Investment SolutionsCopyright 2019 | All Rights Reserved by Sanlam Private Wealth | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Financial Advisory and Intermediary Services Act (FAIS) | Principles and Practices of Financial Management (PPFM). | Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) | Conflicts of Interest Policy | Privacy Statement

Sanlam Private Wealth (Pty) Ltd, registration number 2000/023234/07, is a licensed Financial Services Provider (FSP 37473), a registered Credit Provider (NCRCP1867) and a member of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (‘SPW’).

MANDATORY DISCLOSURE

All reasonable steps have been taken to ensure that the information on this website is accurate. The information does not constitute financial advice as contemplated in terms of FAIS. Professional financial advice should always be sought before making an investment decision.

INVESTMENT PORTFOLIOS

Participation in Sanlam Private Wealth Portfolios is a medium to long-term investment. The value of portfolios is subject to fluctuation and past performance is not a guide to future performance. Calculations are based on a lump sum investment with gross income reinvested on the ex-dividend date. The net of fee calculation assumes a 1.15% annual management charge and total trading costs of 1% (both inclusive of VAT) on the actual portfolio turnover. Actual investment performance will differ based on the fees applicable, the actual investment date and the date of reinvestment of income. A schedule of fees and maximum commissions is available upon request.

COLLECTIVE INVESTMENT SCHEMES

The Sanlam Group is a full member of the Association for Savings and Investment SA. Collective investment schemes are generally medium to long-term investments. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, and the value of investments / units / unit trusts may go down as well as up. A schedule of fees and charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the manager, Sanlam Collective Investments (RF) Pty Ltd, a registered and approved manager in collective investment schemes in securities (‘Manager’).

Collective investments are traded at ruling prices and can engage in borrowing and scrip lending. The manager does not provide any guarantee either with respect to the capital or the return of a portfolio. Collective investments are calculated on a net asset value basis, which is the total market value of all assets in a portfolio including any income accruals and less any deductible expenses such as audit fees, brokerage and service fees. Actual investment performance of a portfolio and an investor will differ depending on the initial fees applicable, the actual investment date, date of reinvestment of income and dividend withholding tax. Forward pricing is used.

The performance of portfolios depend on the underlying assets and variable market factors. Performance is based on NAV to NAV calculations with income reinvestments done on the ex-dividend date. Portfolios may invest in other unit trusts which levy their own fees and may result is a higher fee structure for Sanlam Private Wealth’s portfolios.

All portfolio options presented are approved collective investment schemes in terms of Collective Investment Schemes Control Act, No. 45 of 2002. Funds may from time to time invest in foreign countries and may have risks regarding liquidity, the repatriation of funds, political and macroeconomic situations, foreign exchange, tax, settlement, and the availability of information. The manager may close any portfolio to new investors in order to ensure efficient management according to applicable mandates.

The management of portfolios may be outsourced to financial services providers authorised in terms of FAIS.

TREATING CUSTOMERS FAIRLY (TCF)

As a business, Sanlam Private Wealth is committed to the principles of TCF, practicing a specific business philosophy that is based on client-centricity and treating customers fairly. Clients can be confident that TCF is central to what Sanlam Private Wealth does and can be reassured that Sanlam Private Wealth has a holistic wealth management product offering that is tailored to clients’ needs, and service that is of a professional standard.